Welcome to the American Planning Association's historical archive of PAS Reports from the 1950s and 1960s, offering glimpses into planning issues of yesteryear. Use the search above to find current APA content on planning topics and trends of today.

Grayfields is a collective term used to describe underperforming, obsolete, and often vacant or deteriorating commercial centers. They range in size from small strip centers, to abandoned big box buildings, to entire regional malls.

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PLANNING OFFICIALS

1313 EAST 60TH STREET — CHICAGO 37 ILLINOIS

Suburban shopping centers have come into existence, grown in size, and increased in number not because they offer new products or better stores than are to be found in central business districts, but because they are convenient. Metropolitan areas have grown rapidly in recent years, but the growth has taken place for the most part outside of the central city. Central business districts which were relatively adequate to handle the number (taking their income into account) of people in metropolitan areas a decade and a half ago, are now cramped, crowded and clogged with street traffic.

Shopping centers in suburban areas are nearer the population they serve (in driving time), offer a relatively large (if sometimes inadequate) amount of conveniently located off-street parking, and fit in with the patterns of suburban living described by Burgess and other urban sociologists as long as twenty-five years ago. The farther out from the center of the city that a family lives, the less time the man of the family spends at home. Whatever the social consequences of this situation, it results also in greater dependence on the woman to maintain the day-to-day life of the family. She must run the household and do the shopping, and cannot afford the longer trip to the center of the city — a trip which may have to be taken on slow and crowded public transportation, or by car over congested and hazardous roads with no guarantee that there will be a place to park the car once the central business district has been reached. Shopping center business is drawn almost entirely from people who live within a maximum of thirty minutes driving time over local roads, and most customers live closer.

General definition of a shopping center

A shopping center is a group of retail stores planned and designed for the site on which they are built, located away from the central business district, to serve the shopping needs of new suburban and fringe growth. Every shopping center that we know of has a supermarket (a large retail grocery) in it, and the supermarket is either the largest traffic generator of the shopping center, or is secondary only to a department store in the center. Shopping centers may be distinguished between those that are dominated by a supermarket or retail grocery, and whose secondary store is a drug store or variety store; and those that are dominated by a department store, and whose secondary store is a supermarket, or another department store.

The two types of shopping centers will differ considerably in their area requirements, the number and types of stores, and the annual gross business. They differ also in the trade area served, and the types of shopping needs fulfilled. PLANNING ADVISORY SERVICE Information Reports Nos. 44 and 47 have covered market area analysis for shopping centers and criteria and standards for shopping center stores. The present report shows how the analysis previously described relates to the gross acreage, parking and site design requirements of a shopping center.

Finally the report describes some of the zoning provisions already enacted for shopping centers and comments on some of the problems for city planners raised by shopping centers.

The planner is concerned primarily with the shopper and his (her) trip to the shopping center only after the shopper is driving on the road and up to the time that he enters one of the stores in the center. After that, we leave him to the world of stretchable hose and non-stretchable budgets. The planner is most concerned with four stages of the shopper's trip — the road he travels to get to the center,the point at which he leaves this road and enters the center, the search for an unoccupied parking space, and the walk to the stores.

Shopping center developers, as shown in the earlier reports, must consider many facts which are not strictly within city planning jurisdiction, such as the trade potential of the area surrounding the shopping center, and the types of stores that should be located in a particular shopping center. As final plans for the shopping center begin to emerge, showing the size and layout of the stores, parking area, and service areas, the planner becomes vitally concerned. In fact, we believe there is enough information available on the principles and practices of shopping center development for the planner to be concerned about possible zone locations for shopping centers even before a shopping center is proposed for his area.

This report tries, therefore, to cover the stages of the shopper's progress that concern the planner and indicate the difficulties encountered along the way.

Stage One: The Trip to the Shopping Center

Thirty minutes driving time is currently the accepted limit of the market area of a major regional shopping center, which might serve up to 500,000 people. The area enclosed within the thirty-minute driving time has to be calculated according to the condition and congestion of the streets and is not always in direct ratio to linear distance. Five miles of expressway may be traversed more quickly than five blocks of crowded business section.

Shopping center developers recommend traffic counts of the major streets serving the center, not so much as an indication of the business potentiality, but as a check on the congestion already existing and an aid in predicting the traffic situation after the center is opened. As a matter of self-preservation, developers and architects recommend further studies, including the future road-construction programs in the area, and future housing developments and population movements in the area, so that other effects on business and traffic may be determined.

Once the gross annual volume of business of the center has been estimated, the average number of cars using the center daily may be estimated. Also the peak traffic, in and out, may be estimated, and the time of day at which peak loads will occur may be determined (see below: Stage Two). To the normal present and future traffic loads of the roads serving the center must be added the traffic generated by the center, and the totals must be compared with the capacity of the roads. If the roads do not have the extra capacity to handle the future traffic loads, new road construction should be in the offing, or the center should be located elsewhere. If possible, the site selected for a new shopping center should be adequately serviced by existing public roads.

Stage Two: Off the Road and Into the Center

Crowded highway intersections have long been considered good commercial locations, but the problem of access to the shopping development is receiving much fuller consideration in modern shopping center planning. The key to the access problem is not the volume of traffic passing the center, but the density. As traffic surveys have often shown, the total number of cars passing a given point on a road (the volume) eventually drops as the density gets close to the saturation point. The reason for this relationship is simple. The closer the cars are packed together, the slower they must go. In such dense traffic, as might be said to characterize the rush hour traffic of some Los Angeles freeways or the Chicago Outer Drive, tie-ups and delays are also more frequent, and more costly in terms of highway efficiency. The roads having highest volumes are those on which the cars are spaced further apart and travel at higher speeds with relative safety.

Both the high-density and high-volume roads offer problems of access to the shopping center. On the high-density, fairly slow-moving road, it will be difficult for drivers to maneuver into position to turn off. On high speed roads, ample warning must be given the driver that he is approaching an exit, and the exits into the center must be designed with safety features that take the higher speeds into account.

Few shopping centers will be served by high-speed, limited-access roads. Shopping centers being constructed in developing areas will be served by an existing road network which may not be adequate to handle the traffic that will arise when the shopping center is completed and the area is built-up.

The points of access from the roads to the shopping center should be adequate to accommodate traffic at the busiest hours of the center. Victor Gruen, architect and designer of shopping centers (in "Traffic Impact of the Regional Shopping Center," see biblio) estimates that an exit or entrance with continuous flow can handle up to 750 cars per hour. The peak load of a shopping center can be estimated on the basis of the annual gross income of the center. The problem is three-fold: first, to determine the largest single-day gross business; second, (on the basis of the average purchase per car) to determine how many cars will be in and out of the center on that day; and third, to estimate the number of cars that will enter and leave the center during the busiest hours of that day.

Gruen estimates that a large regional shopping center may expect a peak volume at the rate of 3,000 cars per hour. In such a case, it would seem that four exits are needed to discharge the 3,000 vehicles.

Stage Three: Parking the Car

Parking is the prime convenience advantage of the shopping center over the central business district. In spite of the repetitive statement of this fact, the shopper may not always find the parking space he wants. The shopper wants a space he can find easily, with a minimum of difficulty in moving around the parking area, and one that is located near the store or store group in which he is going to shop. The fault is sometimes with the developers who have underestimated the need for parking space or found the land too valuable to be devoted to parking. Sometimes there are too few parking spaces simply because there are too many people with cars looking for them.

Parking in the shopping center is seen by the shopper as a series of steps:

Leaving the center, he must go through approximately the same steps in reverse, including finding his car which occasionally seems more difficult than it was to find the space originally.

1. Finding the space. Whether the customer finds a space at all depends on the amount of parking space originally provided. The quantity of space is discussed below. Otherwise, the key factors in moving cars around the parkinglot are the lay-out and width of the aisles between the rows of parked cars, especially near the most attractive stores, the department store(s), the supermarket(s), and the drug store(s). How wide the aisles should be depends mostly on whether they will be one-way or two-way. A survey made by the Eno Foundation (Parking Lot Operation), showed that the aisle widths of eight parking lots with one-way aisles averaged 14 feet, and ranged from 7.5 to 21 feet. The low figure of 7.5 is amazing when you consider that the largest 1947 car was over 6 feet, 10 inches wide. For two-way aisles, the width in about twenty parking lots averaged 23.7 feet, and ranged from 16 feet to 37 feet. If the customers park their own cars, as happens at nearly all shopping centers, then the aisles should not be so narrow as to make the task difficult, nor so narrow that one car being parked will temporarily tie up traffic in the aisle. For one way aisles, width should be at least 10 feet; for two way aisles, about 20 feet.

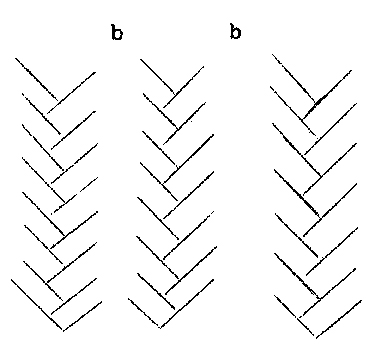

2. Getting the car into the space: Basically, we are assuming that most parking lots are laid out pretty much in the same way. For instance, the spaces and the aisles may be laid out this way:

Figure 1

The narrower aisles (a) are the pedestrian walkways sometimes provided, and the wider aisle (b) between rows of spaces is the aisle for maneuvering the cars. The lay-out may be varied for several types of angle parking, thus:

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

The total parking lot area per car space (including aisles) affects the customer in terms of his difficulty or lack of difficulty in getting into a parking space. The Eno study showed that, for head-in, 90 degree parking, the lots studied averaged 246 square feet per car, with a minimum of 192 square feet and a maximum of 307 square feet. Now 250 square feet per car is considered too small an area for shopping center lots, and 300 is a more commonly accepted figure. Baker and Funaro in Shopping Centers: Design and Operation state that 350 feet is the minimum that can be considered satisfactory. Whatever figure is taken, not more than 200 square feet need be devoted to the space itself. Baker and Funaro recommend a space 9 by 18 feet, and one 10 by 20 feet should be ample. The rest of the area (150 square feet per car by their standards) will be used up in aisles, exits and entrances, and landscaping. No land will be saved by making spaces less than 9 feet wide. Since cars are about 7 feet wide, a smaller space will encourage straddling the dividing lines, and the result will be even fewer usable spaces than if they were 9- or 10-feet wide.

3. Walking from the space to the stores: Once the shopper has safely gotten his car into the best available space, he has only to walk to the stores. We have been assuming that parking would be laid out around the outside of the store group, with the interior mall reserved for pedestrian movement. (See Figures 5–11 below for design of the parking areas in relation to the possible types of store grouping.) Some parking lots have concrete sidewalks between the rows of parked cars (aisles marked "a" in figures 1, 2, and 3). If they are installed, they should be at least 7 feet wide to allow for the overhang of the front ends of the cars, and to allow room for two people carrying packages to pass each other without difficulty.

The Parkington Shopping Center, which is served by a five-story self-parking structure in the interior of the store grouping, is able to boast that no shopper need walk more than 110 feet from his parked car without being under some cover. Covered walkways for shoppers can be an important feature, especially where the parking is spread out considerably, and the weather often inclement.

Multi-story parking garages, because of the relatively high cost per parking space, are not usually recommended by shopping center developers, except where the amount of land is limited and its cost per square foot is high. For shopping center purposes, it is almost necessary that the structure be a self-service parking garage, and this fact raises some problems of design in a multi-level garage, particularly in the size of the spaces and aisles on each floor, and the width and design of the ramps leading to the floors. The Parkington self-parking structure has separate ramps leading directly from each floor to the ground.

How much space?

The quantity of parking space is measured in two ways. The older method is to compare the total area devoted to parking with the net retail area of the stores. Thus, if 50,000 square feet of floor space is devoted to retailing, and 150,000 square feet to parking area, we would say the ratio is 3:1. A more recently used measure is to compute the number ofparking spaces per 1,000 square feet of store space. If we assume that each space takes up a total of 300 square feet of parking lot area (including aisles, landscaping, etc.) then 3.3 cars can be parked for each 1,000 square feet of parking area.

By the old method, a ratio of 3:1 meant that there were three square feet of parking for every square foot of retail space. So, for 1,000 square feet of retail space, we have 3,000 square feet of parking. At 300 square feet a space, 10 cars can be parked in that 3,000 square feet. Therefore, a ratio of 3:1 by the old method, is equivalent to saying 10 spaces per 1,000 feet of retail floor area. Table 1 illustrates the relationship between these two methods of calculating parking in relation to sales area.

With these measures in mind, we can talk about the parking area actually needed for a shopping center. Gruen and Smith have worked out a parking "demand" for a proposed shopping center having 800,000 square feet of floor space and described in Shopping Centers: The New Building Type (see biblio.)

Figure 5

This design is similar to Shopper's World, Framingham, Mass., which is experiencing financial difficulty apparently because no second major store has located at the open end of the mall.

Figure 6

(Similar to Northland, Detroit, Michigan)